October 18, 2022, marks the 50th anniversary of the 1972 Clean Water Act.

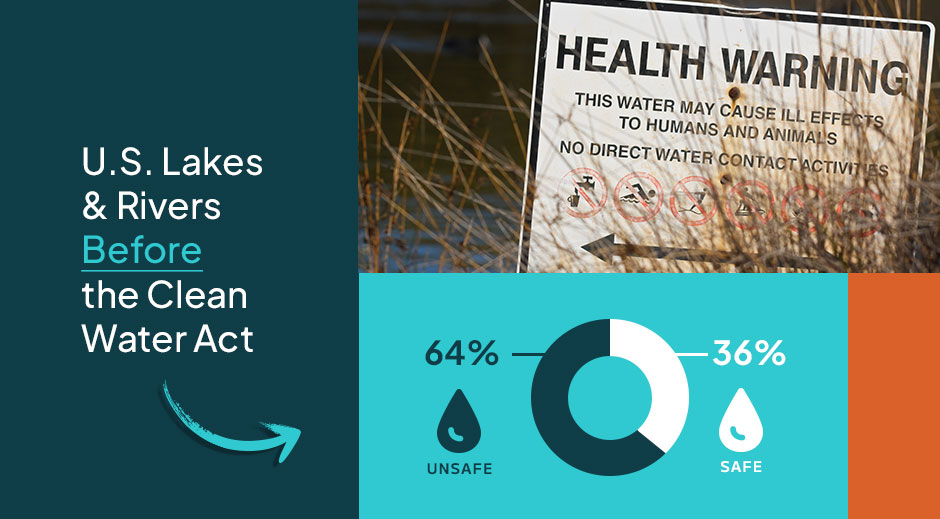

To avoid repeating history, it’s important to remember the conditions that brought about overwhelming public support for the Clean Water Act in the first place. After all, at the time of its passage, only 36% of America’s rivers and lakes were considered safe for fishing or swimming.

But, as we think about the future of clean water, we also need to recognize where the Act has fallen short and left more work to be done.

We’ll be looking at the past, present, and future – but through the lens of the Cuyahoga River Fire of 1969, an event that played a significant role in shaping the modern environmental movement in America.

The fire that sparked an entire movement

When Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River caught fire in 1969, it captured the attention of the nation.

Although the fire did nothing to help Cleveland’s reputation, it did help catapult environmental issues like clean air and clean water into mainstream American consciousness. It drew the nation’s attention to more than 100 years of lax environmental policies – policies that did little or nothing to prevent the river and other waterways from being used as sinks for sewage, chemicals, and other waste.

After the fire, the level of awareness and concern grew to a head. When the first Earth Day was observed the following spring, some 20 million Americans took part in demonstrations across the country.

The politicians heard the outcry, and they acted. In December 1970, Nixon and Congress established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Then, in October 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act with an overwhelming bipartisan majority of 52-12 (with 36 Senators abstaining). It was enough to override Nixon’s earlier veto of the Act.

Once passed, the Act gave the EPA authority to develop water pollution control programs, provided for the construction of sewage treatment plants, and created a system for regulating the discharge of pollutants into U.S. waters.

How a fire cast light on a national problem

Of course, Cleveland wasn’t alone in its lax regulation of industrial and municipal waste discharges. In fact, the Cuyahoga’s lack of uniqueness was one of the main reasons why the burgeoning environmental movement focused attention on it. The river’s very ‘normalcy’ was what enabled it to become a symbol of the many clean water challenges that communities were facing all around America.

Riding the economic boom of industrialization, states and cities across America had been allowing production facilities to dump harmful pollutants in their waterways with little or no consequence. So, by the end of 1969, several cities throughout America’s northeastern and Great Lakes industrial corridors had experienced river fires. Besides the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, there had been fires on the Rouge River in Detroit, the Buffalo River in Buffalo, and the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia.

But, for every waterway that caught fire, there were many more that were just as polluted but didn’t burn. In fact, when the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, it’s estimated that 64% of the nation’s lakes and rivers were not safe for fishing or swimming.

From despair to hope: 50 years of progress

As a symbol of the country’s many environmental woes, the Cuyahoga River fire helped galvanize the American environmental movement, which ultimately led to the Clean Water Act of 1972. Now, that same waterway has become a symbol of hope. It reminds us of how much we can do to turn around the damage done by a century of unfettered pollution.

The Cuyahoga River was once described as having “No Visible Life…Chocolate-brown, oily, bubbling with subsurface gases, it oozes rather than flows.” Thanks to the many improvements that have since been made, all that has changed. Once a dead zone, it is now home to more than 60 distinct species of fish. And, in 2019, the Ohio EPA announced that the Cuyahoga’s fish were finally safe to eat.

Explaining how this transformation happened, Jim White, a former executive director of the Cuyahoga River Community Planning Organization told Cleveland.com, “The Clean Water Act made a big difference in the effort to clean up the Cuyahoga. By directing large amounts of money and enforcing regulations against polluters, the federal government had the muscle to make things happen.”

What’s more, the Cuyahoga is only one of many success stories that have grown out of the Clean Water Act. The Androscoggin River is another triumph. Then, there’s the James River of Virginia, the Ashtabula River in Ohio, the Charles River in Massachusetts, Bass Lake in Wisconsin, and San Diego Creek in California, to name just a few. All these waterways have made dramatic turnarounds since the passage of the Clean Water Act.

Looking beyond the individual successes, a comprehensive study examined 50 million pollution readings from 240,000 monitoring sites. It found that most pollutants had declined by a significant margin since the passage of the Clean Water Act. This was in line with several other studies that found evidence of decreased surface water pollution. What’s more, another study looked at how much change could be attributed specifically to the Clean Water Act. It found that funds granted through the Act “significantly decrease pollution for 25 miles downstream [of wastewater treatment plants] and for 30 years.”

Looking ahead: more work to do

The Clean Water Act undoubtedly has had a positive impact on America’s surface waters. But the Act also included some ambitious goals, which it has failed to achieve. They included (1) ending the discharge of all pollutants into navigable waters by 1985 and (2) making all water safe for fishing and swimming by 1983.

Unfortunately, we are still a long way from achieving those lofty ambitions. A recent study found that about 51% of rivers and streams are still too polluted for swimming, fishing, or drinking. That’s in addition to the 55% of lakes, ponds, and reservoirs and the 25% of bays, estuaries, and harbors that are similarly polluted.

What’s more, future efforts to achieve those original, lofty ambitions could be further hindered. Even as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, the Supreme Court is considering a case that could potentially scale back the protections afforded by the Act.

William Ruckelshaus, the first head of the U.S. EPA, succinctly summarized the ambivalence that many now feel about the results of the Clean Water Act: “even if all our waters are not swimmable or fishable, at least they are not flammable.”

Stay compliant with the Clean Water Act

Through our FTS, OneRain, High Sierra Electronics and Vieux & Associates brands, AEM offers a range of water quality management solutions, including water quality and turbidity data, real-time hydrologic models, stormwater forecasting, and rainfall runoff monitoring. Contact us to find out how our solutions might align with your needs.

| Sources: |

| “Burn On, Big River…Cuyahoga River Fires,” The Pop History Dig. https://pophistorydig.com/topics/tag/river-pollution-1960s/#:~:text=Cuyahoga%20River%20Fires%20In%20late%20June%201969%2C%20the,Cuyahoga%20River%20had%20caught%20fire%20since%20the%201860s. |

| “Rivers That Have Caught on Fire,” WorldAtlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/is-the-cuyahoga-river-the-only-river-to-ever-catch-on-fire.html |

| Adler, Ben. “Supreme Court Could Roll Back Clean Water Protections,” MSN. Oct. 5, 2022. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/supreme-court-could-roll-back-clean-water-protections/ar-AA12DqVp |

| Blakemore, Erin. “The Shocking River that Fueled the Creation of the EPA,” History.com. Dec. 1, 2020. https://history.com/news/epa-earth-day-cleveland-cuyahoga-river-fire-clean-water-act |

| Environmental Works. “History of the Clean Water Act.” April 18, 2018. https://www.environmentalworks.com/history-of-the-clean-water-act/ |

| Guilford, David. “Riverside Towns in Maine Mark 50 Years Under Clean Water Act,” News Center Maine. Sept. 14, 2022. https://www.newscentermaine.com/article/news/local/riverside-towns-in-maine-mark-50-years-under-clean-water-act-rumford-maine-senator-ed-muskie-maine/97-a964c400-032a-412b-be81-8ed2ec02ca95#:~:text=Riverside%20towns%20in%20Maine%20mark%2050%20years%20under,said%20it%20wasn%27t%20a%20matter%20of%20choosing%20sides |

| Keiser, David and Joseph Shapiro. “Consequences of the Clean Water Act and the Demand for Water Quality,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Feb. 2019 (134:1). https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/134/1/349/5092609 |

| Keiser, David and Joseph Shapiro. “U.S. Water Pollution Regulation Over the Past Half Century: Burning Waters to Crystal Springs?” Journal of Economic Perspectives. Fall 2019 (33:4). https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.33.4.51 |

| Kelderman, Keene, et. al. “The Clean Water Act at 50: Promises Half Kept at the Half-Century Mark,” Environmental Integrity Project. March 17, 2022. https://environmentalintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/CWA@50-report-EMBARGOED-3.17.22.pdf |

| Ondrey, Thomas. “Scientists Monitor Cuyahoga River Quality To Adhere to Clean Water Act,” Cleveland.com. April 13, 2009. https://www.cleveland.com/science/2009/04/scientists_monitor_cuyahoga_ri.html |

| Pillow, Jean. “Fishable and Swimmable Waters, Part I,” Ourbetternature.org. February 15, 2008. http://www.ourbetternature.org/fishableswimmable.htm |

| Siler, Wes. “51 Years Later, the Cuyahoga Burns Again,” Outside. Aug. 28, 2020. https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/environment/cuyahoga-river-fire-2020-1969/ |

| Swan, Noelle. “Cleaning Up U.S. Waterways: 5 Success Stories,” The Christian Science Monitor. March 30, 2014. https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/2014/0330/Cleaning-up-US-waterways-5-success-stories |