Hurricane Milton made landfall as a category 3 storm in the late hours of Wednesday, October 9, cutting a path of destruction across Florida. By the time the storm crossed back into the Atlantic on Thursday morning, at least 23 people had been killed or sustained injuries they would not recover from. As the state emerges and Floridians begin the crucial recovery work of rebuilding houses, reopening businesses, and repairing infrastructure, one scary scientific fact lingers: this storm very easily could’ve been worse.

Moving forward, we’ll explore…

- How Hurricane Milton played out across Florida from a scientific perspective

- Why Hurricane Milton had meteorologists very concerned before landfall

- The human and economic impact of Hurricane Milton

- How forecasting and early warnings helped Florida prepare proactively

What happened when Hurricane Milton made landfall?

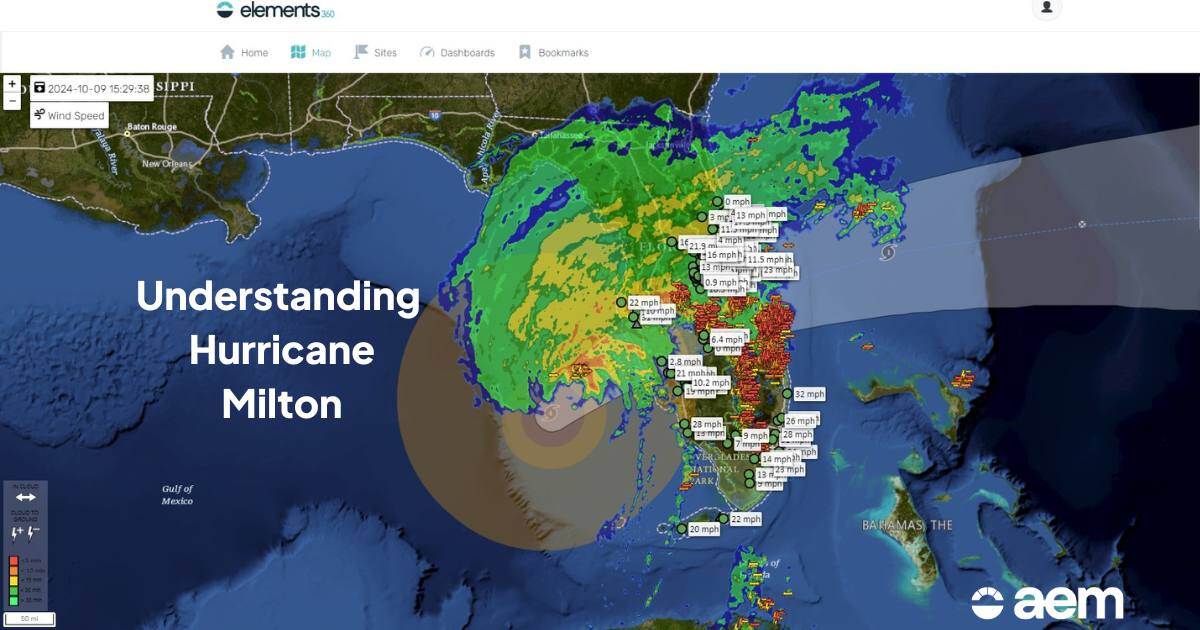

Milton crossed into Florida near Siesta Key, just south of Sarasota, packing 120 mile-per-hour wind gusts and generating five to ten feet of storm surge. Much of the destruction further east was caused by a line of storms ahead of the eye, which generated over 130 tornado warnings from the Florida branch of the National Weather Service.

Here’s a five-minute breakdown of exactly how it played out, presented by AEM Chief Meterologist Mark Hoekzema on the morning of October 10:

Why it could’ve been worse

Milton made landfall as a category 3 storm, but earlier in the week, it was a massive category 5 hurricane off the coast of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. The storm’s intensity rapidly strengthened and weakened a few times as it made its way across the Gulf of Mexico toward Florida, but the wind field kept growing – that told meteorologists that the storm was going to be large, creating the potential for a wide impact zone. In terms of wind speed – which at one point exceeded 180mph – and air pressure, Milton was shaping up to be a historically strong Atlantic hurricane.

As Hurricane Milton traversed the Gulf, there was also some intense meteorological activity occurring within the storm. The storm’s eyewall – the area of strongest wind and precipitation just beyond the eye – was absolutely loaded with lightning. That large volume of lightning as the storm churned toward landfall was another indicator that Milton could be incredibly destructive. (Hurricane Ian similarly exhibited major eyewall lightning in 2022. It’s a trend to track in major hurricanes moving forward.) If that wasn’t enough, it appeared that a tornado-like body formed within Milton’s eye at one point.

|

|

| Intense lightning activity within Milton, captured on Monday, October 7 by the AEM research & development team. | The tornado-like feature in Milton's eyewall, captured on Tuesday, October 8 by SRRadarLoops. |

Thankfully, as Milton approached Florida, it couldn’t help but pull in a great deal of dry air from the west and south because, outside of this storm, it was a very dry week across the continental United States. That dry air weakened Milton and prevented the worst-case scenario, which would’ve included stronger winds and higher storm surge (potentially more than 15 feet) along Florida’s west coast.

While Milton’s landfall wasn’t as bad as it could’ve been on Florida’s west coast, the eastern part of the state was inundated with tornadoes due to the high wind shear ahead of the storm. In fact, the majority of the deaths associated with Milton were in the eastern part of the state, where tornadoes and not storm surge or flooding were the main destructive force. It begs the question: How bad would this storm have been without that last-minute injection of dry air?

Quantifying Hurricane Milton’s impact

As of Monday, October 14, Hurricane Milton’s full economic and human impact are still being tallied, although initial estimates put it in the $160 to $180 billion range. More than 400,000 people are still without power in the Sunshine State, even after a productive weekend for utility workers (last Friday, that number was over 2.2 million people). Many houses across the state have been damaged to the point of total loss or destroyed, including at least 100 homes in St. Lucie County alone.

The true number of homes that are severely damaged or beyond repair is still under-reported, as Floridians and insurance companies are still assessing properties. Fitch ratings currently estimates Milton will account for $30-50 billion in insured losses for property owners across the state.

Even in Tampa, which traditional wisdom holds never gets the worst of hurricanes, Milton shredded the roof of Tropicana Field, which is made from ETFE, a durable Teflon-fiberglass hybrid, and sent a construction crane smashing into the office of the Tampa Bay Times.

Crane collapsed in St. Petersburg, Florida, smashing into Tampa Bay Times office. @StPeteFL posted video showing aftermath of Hurricane Milton. @livenowfox pic.twitter.com/6vWx8FZXY5

— Josh Breslow (@JoshBreslowTV) October 10, 2024

The power of early warnings

Another reason Florida avoided the worst-case scenario with Milton was the robust tracking of the storm. Thanks to the work of the NOAA, National Weather Service, and consulting meteorologists, government and business leaders in the storm’s path could be proactive with shutdowns and evacuations.

The local and national media also stepped up early in the week to communicate the severity of the forecast and scale of the storm. That effort informed and built buy-in with the public, which significantly reduced the number of people and vehicles in harm’s way when Milton arrived overnight.

Even now, that process is ongoing, as meteorologists track the development of other storms in the Atlantic Basin. (The next potential named system this year will be “Nadine.”) This tropical storm season has shifted in three weeks from relatively quiet to memorably destructive, and many meteorologists believe we might not have seen the last of it yet.

As Florida recovers from Hurricane Milton and Hurricane Helene, communities across the United States and globe need to focus on how they can be prepared for the next severe weather event. In the face of these powerful hurricanes and the wind, lightning, and even tornadoes they bring with them, it’s crucial for meteorologists, civic leaders, the media, and area businesses to come together to keep people safe and protect the community. At AEM, we call that approach collaborative resilience, and we believe it's the most important work happening right now.