Sadly, the Maui wildfires will go down in history as one of the great U.S. tragedies. With 115 deaths confirmed so far, the disaster has already claimed more lives than any other U.S. wildfire in the past century. And with 288 people still missing, the death toll could continue to rise.

Communities all around the world need to learn from what happened in Maui. Because many are primed to follow in Hawaii's footsteps.

As environmental risks continue to escalate, communities are underestimating the threats they face, which is leaving them with dangerous gaps in their systems for mitigating these risks. And the lesson, here, is not confined to wildfire risk; it applies to a wide spectrum of environmental risks.

There were gaps in Maui’s early warning system

On the surface, Hawaii’s wildfire early warning system appears to have had some critical gaps that were exposed by the rapidly spreading flames.

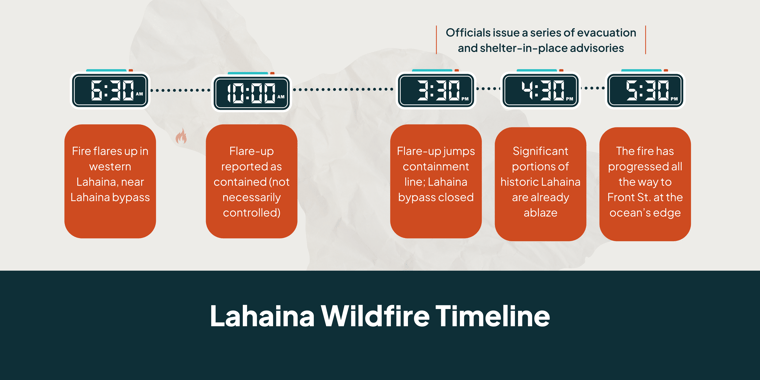

According to a timeline pieced together by the Associated Press, an earlier fire near the town of Lahaina was reported as contained (but not necessarily controlled) by 10 a.m. on August 8. Then, by at least 3:30 p.m., that fire escaped the containment line. After that, winds from Hurricane Dora pushed the fire all the way to the seaside in only a couple of hours, killing many as they sheltered in place or sat in gridlock on the closed evacuation route.

As fires threatened Lahaina, officials claim they sent emergency warnings via radio, television, and mobile alerts (all of which depend on intact power and cellular service). However, some residents and visitors have raised questions about the content, timing, and accessibility of those warnings.

- In a statement to CNN, Lahaina resident Allen Vu said, “On my cell phone, we had warnings of strong winds and possible fires…But no real…warning like the Amber Alerts or those storms that we would normally get that would vibrate and make loud noises from our phones.”

- Others say that when the evacuation orders finally did come, they came too late. The New York Times reports that tourists said they received a mobile alert at 4:17 p.m., a full 47 minutes after one of the major evacuation routes had been closed because of a downed power line. And the Associated Press reports that the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency posted on social media at 4:29 p.m. that Maui Emergency Management was issuing an immediate evacuation for a neighborhood that was already ablaze and that some residents had fled a full hour earlier.

- And, with interruptions to power and cellular service, there is some question about how many in the affected areas could even receive the messages that were sent.

Another source of contention is over the decision not to utilize the state’s extensive siren system. Five of those sirens are located in Lahaina, and two of the five have solar power, so they could have been triggered even during the power outages. Officials have defended the decision not to sound the sirens because they are associated with incoming tsunamis, and residents are trained to flee toward the mountains when they sound. This could have prompted residents to flee straight into the path of the fire.

Regardless of what the final analysis may reveal, one thing is clear: there were gaps in the early warning system that caused many in the affected areas not to get the notice they needed in time to seek safety.

The root cause: Hawaii underestimated its wildfire risk

Talking to Reuters, Adam Weintraub of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency put his finger on the heart of the problem: “A lot of our systems were built for a different climate and a different set of hazards that moved a little slower.”

Weintraub’s statement brings us to the underlying issue: Hawaiian officials appear to have underestimated the state’s wildfire risk.

HAWAII'S WILDFIRE RISK HAS BEEN GROWING

Although wildfires in Hawaii are not new, the problem has historically been a relatively small one and associated mainly with volcanic activity. However, Hawaii’s climate has become drier. And as agriculture has given way to a tourism-based economy, more than 25% of the land has been taken over by invasive, fire-prone grasses and shrubs. As a result, the state’s fire risk has grown.

As far back as 2015, it was noted that an average of 0.5% of the state’s land area was burning each year, which was equal to or greater than the proportion of land burned in any other state. The heightened risk was further underscored by a 2018 wildfire that struck the same general area of Maui. Although no one died in the 2018 fire, it was a near miss for Lahaina and still destroyed 21 structures, 30 vehicles, and more than 2,800 acres. In the wake of that incident, residents called for officials to make wildfire a bigger priority.

HAWAIIAN OFFICIALS DID NOT ACKNOWLEDGE THE GROWING WILDFIRE RISK

Yet, as recently as 2022, Hawaii’s emergency management agency released a report detailing the natural disasters most likely to threaten residents. The report focused heavily on tsunamis, earthquakes, and volcanic hazards. Wildfires received minimal attention as they were described as posing a “low” risk to human life.

Without an accurate picture of the risk, wildfire suppression budgets in Hawaii have tended to be inadequate. The limited budgets that have been available have typically covered only the costs of fighting fires and have left little or nothing to put toward proactive prevention and mitigation measures. And in the absence of an accurate picture of the risk, officials were not prepared for the various wildfire scenarios that they could realistically encounter – including the scenario that materialized on August 8 in Lahaina.

Beyond Hawaii: Environmental risks are escalating

It would be all too easy to isolate ourselves from the disaster in Maui by attributing it to poor decision-making. But that would be a dire mistake. Communities across the United States and abroad share more in common with Hawaii than they might think.

First, Hawaii is not the only place where wildfire risk is increasing. According to a 2022 study by the National Science Foundation and Colorado State University, U.S. wildfires have quadrupled in size and tripled in frequency since the start of the 2000s. Or, if we look at the average acreage burned annually, it was 68% larger from 2017 to 2021 than it was from 1983 to 2016.

Secondly, wildfire isn’t the only environmental risk that is escalating. For example, as the earth’s baseline temperature has continued to rise from its pre-industrial level:

- Heat waves have become 2.8x more frequent.

- Droughts are 1.7x more frequent.

- Severe rainstorms have become 1.3x more frequent.

And, if Earth’s baseline temperature continues to rise at the rate projected by scientists, then by 2030:

- Heatwaves would become 4.1x more frequent.

- Drought would be 2x more frequent.

- Extreme rainstorms would be 1.5x more frequent.

The relationship between extreme rainfall and flood risk is complex and not perfectly linear. However, current research indicates that extreme flood events will increase in both frequency and intensity as the earth’s baseline temperature continues to warm. It’s the more moderate flood events (i.e., the ones that communities tend to be more prepared for) that are more likely to decline in frequency.

Communities are not keeping up with growing environmental risks

Unfortunately, many current systems for dealing with environmental risks simply are not designed to keep up with the escalating nature of these risks.

For example, many state budgeting processes are failing to keep up with growing wildfire risk and its associated costs. A recent Pew report looked at how 6 states budget for wildfire costs. While there were differences, all of them relied on backward-looking estimates based on past suppression costs to decide how much to budget. While such an approach may work well when fire suppression costs are relatively stable over time, it has a tendency to come up short when the trend is toward larger, more destructive, and more frequent fires.

And, that’s exactly what we are seeing. Almost every state in the Pew study recently experienced fire seasons in which budgets for fighting wildfires fell short of what was needed. And while many states have methods for securing emergency appropriations, those processes often obscure the full cost of fighting wildfires and sometimes come at the cost of sacrificing proactive wildfire prevention and mitigation activities.

Unfortunately, this issue isn’t confined only to wildfire risk. Consider the U.S. system for mitigating flood risk to homeowners. Anyone who uses a federally backed mortgage to purchase a property with at least a 1% chance of flooding each year is required to purchase flood insurance. The system is based on FEMA flood maps that indicate where the high-risk properties are located. But the flood maps are developed by looking backward at historical flood data.

The problem is that as more extreme floods become more frequent, FEMA’s flood maps are becoming outdated faster than new ones can be produced. What’s more, the maps focus on river and coastal flooding and fail to account for flooding caused by extreme rainfall (which is itself becoming increasingly common). As a result of problems like these, a 2017 study by Homeland Security concluded that 58% of all FEMA flood maps were considered inaccurate or out of date.

What does this mean for communities and homeowners that rely on FEMA flood maps? According to 2020 modeling by First Street Foundation, of the 14.6 million properties that may actually be at high risk of flooding, fewer than 60% are designated as high risk by FEMA flood maps. This aligns with FEMA’s acknowledgment that more than 40% of claims through the National Flood Insurance Program come from outside of designated high-risk areas.

In short, at least some of the current systems for mitigating environmental risks like wildfires and floods are not working as well as they should because they share a common problem with Maui’s early warning system; they rely too heavily on backward-looking environmental risk assessments that fail to adequately factor in the continued escalation of those risks.

Toward a better approach to assessing environmental risks

To deal effectively with environmental risks, communities need an accurate picture of what they are dealing with. In a world where those risks are escalating, communities can no longer get that accurate picture by looking only at what has happened in the past.

To fully understand the magnitude of the risks they are facing and prioritize them correctly, communities need to study the historical data with a forward-looking eye. They need to use the data to glean the rates at which different risks may be changing. Then they need to project those rates of change into the future. What’s more, communities need to recognize that even the rates of change are dynamic and can change over time.

Otherwise, you run the risk of being caught unprepared when the next environmental disaster strikes.

Of course, any reassessment of environmental risk and its operational implications will necessarily involve a significant amount of specialized expertise. So, for many organizations, the most natural place to start is to bring in an outside expert to provide a fresh, impartial perspective on where there might be opportunities for improvement. That’s why AEM offers a free initial consultation to begin the process of evaluating your level of weather-readiness and identifying potential gaps in your preparations.